“I do not let the word ‘death’ bother me…”

In 1997, I was hired by a Hong Kong film company called Media Asia. My wide ranging portfolio with them included working as a scriptwriter on films like ‘Gen-Y Cops’ (2000) and as a producer on two documentaries for action star Jackie Chan. I was also the company’s Hong Kong film expert in residence. They needed someone with that particular attribute on their staff because the company then controlled the distribution rights to the bulk of the Golden Harvest film library. This included all the films the studio had made between ‘The Angry River’ (1971) and ‘Crime Story’ (1993).

One of my missions was to supervise the copyright registration of the Golden Harvest film library with the US Library of Congress. This meant I got paid to sit and watch pretty much every movie the studio ever made. This was something that I had being paying to do for many years, so I felt I’d landed on my feet at Media Asia.

The company’s storage facility was located in an industrial area of Hong Kong Kowloon Bay. It was called the SFC (Something Facility Centre), and presided over by a wizened crypt keeper named Larry. He headed a surly, scruffy staff. Though situated on an upper floor of a featureless factory building in Kowloon Bay, this windowless fortress always had a subterranean feel. It seemed that the whole team pawed their way each day through film and tape, mole like, and rarely saw sunlight. Housed within these airless confines was a true treasure trove of classic Hong Kong movie material.

A little history: [redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Back when I first joined Media Asia, the company had just taken delivery of all the relevant film and promotional materials from Golden Harvest studios. These had been shipped, in a state of some disarray, to the aforementioned SFC facility in Kowloon Bay. Larry and his far from merry men were charged with organizing the film elements and attendant publicity materiel, cataloguing what was and wasn’t delivered and undertaking some very necessary restoration work. It felt like Golden Harvest had delivered the materials rather begrudgingly. Perhaps they realized the deal wasn’t as good for them as they’d initially anticipated…

The Golden Harvest archive that did survive remains a real treasure trove. I suspect that a significant amount of material didn’t make the trip from the company’s Hammerhill Road studios to the Media Asia warehouse in Kowloon Bay. These precious elements were almost certainly destroyed when the Golden Harvest studio itself was demolished in 1997. Prior to that demolition, I saw visual evidence of this. Some Japanese fans bribed the night watchman and thereby won access to the old Golden Harvest storage warehouse. Being Japanese, they had actually taken photos of themselves during this illegal night-time jaunt. Seriously, how many American thieves would stop to take selfies? This raid took place after the transfer of materials to Fortune Star but before the delivery to Media Asia. The images taken by the fans revealed many boxes of memorabilia that remained behind at Golden Harvest studios. Whatever materials were left behind eventually found their way to New Territories landfill. Damn it.

Given all of the above, it was only a combination of luck and mismanagement that allowed one particular aspect of Bruce Lee’s legacy to survive. As mentioned in Chapter Ten, Bruce Lee had, in 1972, shot footage for a film to be called ‘Game of Death’. After shooting over several months, Lee suspended production on the project, presumably temporarily, in order to make ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973). The footage Lee left behind was edited, years after his passing, into the Golden Harvest production ‘Game of Death’ (1978). Further footage from Lee’s original ‘Game of Death’ shoot was featured in a documentary entitled ‘Bruce Lee the Legend’ (1984). Eager fans, myself included, pored over the material used in the 1978 film and the documentary, as well as the available still images from Lee’s ‘Game of Death’ shoot. We were all trying to interpret Lee’s ‘lost’ original vision for his film.

So what did we manage to deduce? Bruce Lee had shot sequences where his character and his two fellow ‘challengers’ (Chieh Yuan and James Tien) fight their way up a multi-storied tower or pagoda. Each level of the pagoda is guarded by the master of a different martial discipline. The only levels Lee actually filmed featured Dan Inosanto (kali), Chi Hon-tsoi (hapkido) and basketball legend Kareem Abdul Jabbar (the ‘unknown’ style). It seemed highly unlikely that Bruce had actually filmed the scenes set on any of the other floors of the tower. If he had done so, film stills showing the ‘lost’ scenes would have leaked out. We knew from the ‘Bruce Lee the Legend’ (1984) documentary that Bruce had shot exterior footage in the Hong Kong New Territories. It showed his student Dan Inosanto and hapkido experts Chi Hon-tsoi and Whang In-shik demonstrating their skills against various karate gi-clad stuntmen. Presumably, more footage had been filmed than that which was included in ‘Bruce Lee the Legend’ (i984)? What was it and where was it kept? There were stills of Lee posing with Inosanto and the same stuntmen, shot at the same locations. Had Bruce actually filmed any of this ‘outdoor’ footage of himself for his ‘Game of Death’?

I think it unlikely that Lee actually filmed himself at this exterior location in Hong Kong’s Fanling district. This was to be footage screened for the full group of Challengers before they left for the ‘Island of No Guns’. It would have been expanded to include material showing the other Guardians. Except for Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, playing the Unknown, as his character was, well, Unknown…

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Flash forward two decades to my tenure as Media Asia’s Bruce Lee expert in residence. During one of my first visits to the SFC facility, I asked Larry the crypt keeper what Bruce Lee material they had received from Golden Harvest? He showed me a list that included the Bruce Lee films, in various languages, as well as their relevant trailers. It was while I was scanning this document that he mentioned the mystery surrounding some other reels of film, marked only ‘Game of Death’, received from Golden Harvest. This had been duly transferred from celluloid to Betacam tape: would I like to look at it?

There has long been a rumor circulating that I dug up the missing ‘Game of Death’ footage from beneath a pile of chicken dung on the Golden Harvest back lot. It’s such a great story that I’m bitterly disappointed it isn’t true. I believe it was the case that some of the 35mm prints of the Harvest films were found to have been stored in the studio washrooms, so perhaps that’s where the rumor started. The more prosaic reality is that the SFC staff simply put a bulky Betacam into the relevant machine and pressed ‘Play’, and I watched, in amazement, as, eventually, Bruce Lee’s original ‘Game of Death’ dailies unfolded before my eyes.

The contract Golden Harvest had with Fortune Star called on the company to deliver the various completed versions of their films, as well as their attendant trailers and other promotional footage. This makes their delivery of the 1972 ‘Game of Death’ dailies something of a mystery. What seems to have happened is that, while Golden Harvest were preparing the materials for the transfer to Fortune Star, one of their staff, believing the ‘Game of Death’ reels to be some necessary promotional material, simply loaded it with the other canisters of film. And let’s hear it for that guy!

It’s easy to see how such a mistake could have been made. [redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

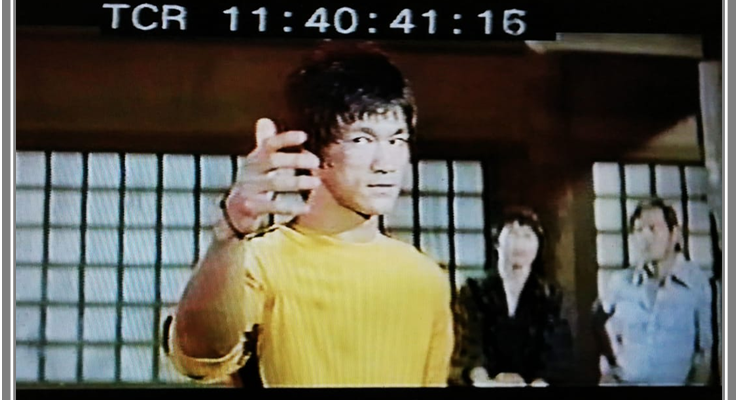

Suddenly I was watching actor James Tien running up the stairs of the pagoda and onto the floor guarded by Dan Inosanto’s Guardian. In take after take, Tien runs up again and again and again, and then attacks Inosanto’s character again and again and then, after a few versions of this, Dan responds, attacking Tien more ferociously than he ever does Bruce Lee’s character in their match. And, before my eyes, Bruce Lee’s original ‘Game of Death’ unfolded, shot by shot. I realized I was viewing the dailies left behind by Lee when he downed tools in October 1973 to start work on ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973).

And suddenly I was back at the Formica desk of my old room in 28, Thorpe Avenue, Peterborough, our family home, on a sunny afternoon, painstakingly putting together notes and images on ‘Game of Death’, the poster from the 1978 film on the wall beside me, with Bruce Lee in all his yellow track suited glory. How rarely the heroes of our youth come back to speak to us in later age, but, that day, in the spartan surroundings of the SFC screening room, I felt a dream lost for long years suddenly come alive before me. How many times had I analyzed the extant 1972 ‘Game of Death’ footage and its attendant images, searching for fresh meaning? Here, now, was the Rosetta stone of lost Bruce Lee footage, through which all those long ago questions would finally be answered.

The first thing that struck me about Lee’s dailies is how polished they were. The Bruce Lee footage used in the 1978 ‘Game of Death’ had been edited in a very haphazard fashion. Seeing Lee’s original vision unfold, it became clear how clean and crisp Lee’s original fight scenes were and how witty he was becoming as a film-maker. There were some clever shots that Clouse could easily have used in his version of the film. For example, when Lee’s character first confronts Kareem Abdul-Jabbar, the latter is sitting down in a rocking chair. When Lee charges forward, Abdul-Jabbar kicks him in the chest, leaving the now famous footprint on Lee’s yellow cat suit. Lee flies back, lands and then we see him from Abdul-Jabbar’s perspective, and the image rocks in time to the taller man’s rocking chair. It seems Clouse somehow felt he had to impose his own directorial style, such as it was, on the whole of the 1978 ‘Game of Death’.

But I get ahead of myself. The Inosanto scenes had been shot over the 27th and 28th of September, 1977. There was a slight frustration that the beginning of the Inosanto scene was still missing. Where was Chieh Yuan running up the stairs, carrying his heavy log weapon? Where was Dan’s Moro rising to face him? This last shot was used in the 1978 ‘Game of Death’ but was missing from these dailies. Where was the fable Log Scene itself? The footage I found cuts in with the Chieh Yuan character already unconscious in the background.

In this long unseen footage, I watched an impressive Dan Inosanto, as The Moro, overpower James Tien’s cocky Stylist. It’s as Inosanto’s character rat-a-tat-tat-tats a charging double stick attack on James Tien that, finally… The Dragon rises. Bruce Lee runs up the stairs and whips out his green bamboo sword, not so much entering the scene as slicing his way into the film. Up until that moment, it was in the back of my mind that this found footage might suddenly, tantalizingly, cut right before Lee’s character makes an entrance.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

This was a unique chance to see Bruce Lee in the act of creation. There’s often a sheer joy to his movements as he crafts this film with complete freedom. He has no limitation but his own limitation, his yet relative inexperience as a director. Lee’s growth was evident in every shot. In the interstitial moments, you can see occasional flashes of frustration, with himself and others. It’s an unusually intimate shoot. One set, redressed three times, and a very limited cast and crew. It feels a lot more like an art film, something experimental, than it does a studio film for a major star. Viewed in this raw footage, the sheer speed of Bruce Lee becomes evident. He’s like The Flash in his yellow suit, all he needs is a lightning bolt on his chest.

Even after I first screened the full surviving 90 minutes of dailies, it was evident that there were still some unanswered questions. There were no hints as to the action that had preceded the scene set on Dan Inosanto’s floor of the pagoda. The initial combat scene between Dan Inosanto and Chieh Yuan was also missing. The empty hands section of their fight had been used in the ‘Bruce Lee the Man and the Legend’ (1973) documentary. The opening to it, where Chieh Yuan wields a log like weapon against Inosanto’s kali sticks, was apparently still lost. I have my own theory regarding that particular piece of footage. There were originally two versions of the ‘Bruce Lee the Man and the Legend’ (1973) documentary, an English and Mandarin one. The latter seems to have been lost. I suspect that, when these two versions were edited, someone couldn’t be bothered to duplicate a section of the Chieh Yuan/Dan Inosanto fight. Instead, he, or she, just hacked it in half and stuck the weapons section in the Mandarin version, and the empty hands part in the English one. They simply never returned the footage to the appropriate can of ‘Game of Death’ dailies. Well, that’s what I believe, and it makes as much sense as the other extant versions explaining the Mystery of the Lost Log…

Over the years, I’ve heard various rumors regarding this particular piece of missing footage, known to fans as ‘The Log Fight’. One was that Bruce Lee had given a copy of the fight, on film, to Dan Inosanto before Dan left Hong Kong in 1972. Inosanto himself denies this, and it would have been an unusual gesture anyway. Dan would not have had access to a 35mm projector, and a clip from an unfinished, unreleased film would have had little value. And Bruce presumably didn’t anticipate his own premature demise. Lee did gift Dan some of the weapons his character used in the fight, which makes rather more sense.

Another story had the Log footage being in the possession of the late John Ladalski, a longtime resident of Hong Kong’s notorious Chungking Mansions. Ladalski was a real local ‘character’ in his own right. Quirky, fringe bald and perpetually impecunious, the Illinois native clung to the Asian film industry like a limpet. He had a ten year career working as a supporting player in Hong Kong movies, before drifting off through other parts of Asia. Ladalski had only a tenuous connection to any lost Bruce Lee footage. He didn’t show up in Hong Kong until after Lee’s demise. John Ladalski made a brief appearance in the 1978 ‘Game of Death’ (1978), and met Dan Inosanto in the context of them both appearing in a Taiwanese Brucesploitation film, ‘The Chinese Stuntman’ (1981). Neither connection made him a likely recipient of ‘The Log Scene’. Besides, poor John was usually so impoverished, he would certainly have cashed in on such a treasure years ago.

So what was the final destination of the fabled ‘Log Scene’? My bet is that whatever remained of it at Golden Harvest, mislabeled and forgotten, went to some New Territories landfill, the same one that holds whatever else lay in the long-demolished studio warehouse. ‘The Log Scene’ now lies among the trees, lost for all time.

There was one big surprise at the very end of the surviving footage. Contrary to my expectations, Lee’s character never climbs the stairs to the highest level of the pagoda. Instead, he rises from the inert body of The Unknown (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar) and then just staggers back down the different floors he’s just fought so hard to climb. As a youngster, I had dreamed, literally, about what Lee’s character would find at the top of the pagoda. It was a disappointment to come away from all those dailies still not knowing.

With any other abandoned movie project, you could just look at the script and ascertain what had been left unfilmed. In the case of ‘Game of Death’, it seems there never was a complete script, in the accepted sense of the term. As part of his invaluable contribution to the preservation of Lee’s legacy, the Canadian writer John Little discovered a detailed story outline in the Lee family files. This is in Bruce Lee’s own hand writing and drawings, and lays out Bruce’s vision for his ‘Game of Death’.

That tale plays out as follows: Hai Tien (Bruce Lee) is a former martial arts champion flying from Hong Kong to Korea. He’s accompanied by his sister and younger brother.

After the family lands at Korea’s Kimpo airport, Hai Tien is coerced by a powerful gang boss into joining a ‘Mission: Impossible’-style team to raid a six story pagoda. The thugs hold his sister and younger brother captive, forcing Hai Tien to cooperate.

The pagoda in ‘Game of Death’ is located at a temple, based on the one at Pochusa temple in Korea. Pochusa is located at Songnisan National Park in North Chungchong Province. Though the pagoda depicted in Bruce’s sketches evidently has five floors, the Pochusa one, known as Palsangjon, is six stories high. It was built in the early 1600s and remains the only large wooden pagoda in Korea. Disappointingly, the actual pagoda has a hollow interior. It has walls that hang, like a bell, from a central pillar, making it virtually earthquake proof. Even in 1973, international audiences might have wondered why the gang boss didn’t just storm the place with armed mercenaries. Like Han’s island in ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), this was a temple where no guns were allowed, even for master criminals.

Hai Tien has with him several fellow Challengers. They include The Brawler (Chieh Yuan) and The Stylist (James Tien). Their scenes for the film’s finale were actually filmed. The other characters Lee created for the film included The Westerner, to be played by former 007 George Lazenby. Lee had spent a few days getting to known Lazenby while the latter was in Hong Kong. Strangely, given that Bruce must have been one of the most photographed men who ever lived, there isn’t a single extant image of he and Lazenby together. Lee was scheduled to meet George and producer Raymond Chow on what turned out to be the last night of Bruce’s life. Lazenby never got to shoot any footage for ‘Game of Death’. He remembers that, while he was in Hong Kong, he’d receive late night phone calls from Bruce during which Lee would describe scenes for the film, still a work in progress, at great length.

A non-fighting member of the team, The Locksmith, would have been played by Lee Kwan, one of Bruce’s favourite comic actors. The final, unspecified member of the team would be a fighter motivated by the need to earn money to pay for a life-saving operation for his mother.

The role of The Brawler was originally intended for Sammo Hung. When, to Lee’s frustration, Hung proved unavailable, he replaced him with the muscular Chieh Yuan. Chieh had been a supporting player in a string of Shaw Bros films, including the Wang Yu classic ‘One-Armed Swordsman’ (1967) and the US theatrical hit ‘King Boxer’ (1972) AKA ‘Five Fingers of Death’. Lee’s concept for the character was that The Brawler would tackle every challenge head on, and lack the tactical sense to survive. James Tien, Lee’s co-star from ‘The Big Boss’ (1971) and ‘Fist of Fury’ (1972), was perfectly cast as the wily Stylist. The rationale for his role was that he would try to use strategy to overcome each obstacle, but eventually lack the fighting spirit to succeed.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Once on the island, the team’s first challenge would be for them to fight their way through the fifty karate experts. These would be played by “a group of stuntmen”, according to Lee’s notes. The karate experts are guarding the approach to the pagoda, and the performers would have included Peter Chan, Bee Chan Wui-ngai, Lam Ching-ying and Wu Ngan. These were the same guys Lee shot for the ‘outdoors footage’ mentioned above.

After surviving this first test, four of the Challengers would enter the pagoda itself. Apparently, the pagoda has been locked from the outside, and The Locksmith has to help the Challengers enter. Each level of the pagoda is protected by a guardian skilled in a different style of martial art. And you have to wonder how the various Guardians came and went, given they were all locked inside. And what did they do there all day? It can’t have been much fun stuck on one floor of a pagoda, waiting for someone to kill. None of the different levels look particularly comfortable to hang out in.

The lowest floor was to be guarded by Whang In-shik, a Korean hapkido expert. Lee had fought Whang In-shik in ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972). Appropriately, Whang would play an expert in a style favoring kicking techniques. Whang In-shik didn’t shoot any footage for his floor of the pagoda, but he does appear in the 1972 ‘Game of Death’. The hapkido expert doubles for Chieh Yuan for the wide shots where The Brawler gets thrown around by Chi Hon-tsoi character. And he’s featured in the exterior footage Bruce shot at Fanling to promote the project.

The Westerner would be injured during the karate battle, but Hai Tien (the Bruce Lee character), The Brawler and The Stylist would succeed in defeating The Kicker, and continue to the next level.

The second level would be protected by an expert in Mantis kung fu. Lee had tapped one of his earliest Seattle students, the Japanese-American Taky Kimura, to play this role. Despite Taky’s trepidations, Bruce persuaded Kimura to participate, and went as far as to send him an airline ticket. Lee had also shot test footage of his senior Wing Chun kung fu brother Wong Shun-leung towards his being cast in ‘Game of Death’. This test was filmed on the weapons chamber set built for ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), and showed Wong Sifu performing the kind of close range Wing Chun techniques his art is famous for.

As Hai Tien and The Stylist fight The Mantis Master, The Brawler races up to the next level to face a Filipino escrimador, The Moro, played by Lee’s student and friend Dan Inosanto. It’s at this point that the footage Lee filmed in 1972 begins. As mentioned above, most of the footage of the initial clash between Chieh Yuan and Dan Inosanto seems to have been lost. A clip from the very beginning of the sequence, showing The Moro sitting on a wooden throne, was used in the 1978 version of ‘Game of Death’. The footage of Chieh Yuan’s character coming up the stairs and attacking Inosanto remains missing, as does the famed ‘Log Scene’. In this sequence, The Brawler attacks The Moro using a log-like length of wood, but proves no match for Inosanto’s double sticks. After being disarmed, The Brawler is dispatched by a flurry of empty hand techniques from The Moro. This and the opening shot of Inosanto are the only extant footage from the Brawler/Moro scene.

The Stylist arrives in time to see The Brawler go down for the count. It’s here that the dailies Lee left behind begin. The Stylist twirls his own weapon, a short stick. There was to have been a weapons rack on the floor below, from which each Challenger would use an implement fitting his personality: the Brawler picks a heavy log, the Stylist a close range weapon and Lee’s Hai Tien two flexible weapons, a whip and a nunchaku. For the 1978 version on ‘Game of Death’, the production built a weapons rack beside a mockup of the pagoda stairs. This was to justify explain Billy Lo having weapons with him when he faces ‘Pasqual’ (Dan Inosanto).

The Stylist then takes on The Moro. He, too, proves no match for the Filipino fighter’s ferocity. Lee the director frames the sequence nicely, almost a POV shot from the top of the wooden stairs. We see a Chinese sign on the wall behind The Moro, which reads ‘Fu Deen/The Tiger’s Palace’. The scenes set on this floor of the pagoda were shot between the 27th and 30th of September, 1972.

Lee himself runs up the stairs, carrying his thin bamboo rod and a concealed pair of nunchakus. In the dialogue exchange that follows, Hai Tien suggests that The Moro allow the stunned Brawler to be pulled to safety so Hai and The Moro can fight. The Moro agrees, but insists that all the Challengers must stay away from the staircase leading to the floor above. The Stylist pulls The Brawler to safety, and then Lee and The Moro engage in a protracted weapons duel, with Lee providing a running commentary about the ineffectuality of the Filipino fighter’s fixed, flashy routines.

Lee’s bamboo ‘sword’ proves too flexible for The Moro’s sticks. Inosanto himself remembers that, each time Lee would make his initial attack, Dan would accidentally snap the bamboo weapon as he blocked it. Finally, Lee stepped up and whispered in his ear. “This is my last one. Don’t break it!” The duel progresses to nunchaku against nunchaku. Lee succeeds in enraging The Moro. For the 1978 ‘Game of Death’ (1978), director Robert Clouse had, understandably, been forced to cut away any footage where we see James Tien and Chieh Yuan in the background. The most memorable of these deleted shots has Inosanto perform a series of acrobatic rolls across the floor as The Moro tries, in vain, to hit his opponent in the shins.

Hai Tien disarms The Moro before finishing him off. It’s never clear why Lee’s character had to kill The Moro, when he could simply have knocked him out. Throughout the footage, there’s a casual nature to the way Hai Tien dispenses violence, an absence of any ‘emotional content’, a demeanor very different from that of the characters Lee played in his other films. One wonders what audiences would have made of this arch, cold-blooded Bruce Lee character, had he lived to finish his ‘Game of Death’.

There’s then a non-verbal exchange between Lee and the other two Challengers, The Brawler is appreciative, The Stylist is dismissive. The three of them continue up to the next floor of the pagoda.

There, they encounter The Hapkidoist (Chi Hon-tsoi). Chi’s character presses a switch on the wall behind him, activating a red light on the ceiling. He then obligingly reminds the intruders that “red means danger”, before advising them to leave. The light is used to signal The Unknown (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), situated on the floor above, to expect company.

Very sportingly, Hai Tien throws away his nunchakus when faced with an unarmed foe. The Brawler attacks first, and is thrown around the room by the Korean Guardian. At this point, there’s damage to the original negative of the ‘Game of Death’ footage, causing Chieh Yuan to be bathed in a green glow. When I first saw the footage, I thought this might be an intentional effect. Lee maneuvers the crafty Stylist into entering the fray, but even Tien and The Brawler together prove no match for The Hapkidoist. When Chieh Yuan’s character is thrown around the floor by The Hapkidoist, he’s doubled by Whang In-shik.

Lee uses a couple of Sergio Leone sized close ups to show Hai Tien and The Hapkidoist sizing each other up. It’s an almost Eisensteinian device. Lee’s eyes have an extraordinary power, and seem even more powerful when juxtaposed with a matching shot of the duller orbs of Chi Hon-tsoi.

Finally, Lee’s Hai Tien steps up to take on the Korean master himself. [redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

While Lee and The Hapkidoist are fighting, The Stylist coerces The Brawler into running up the stairs to the next floor. Moments later, The Brawler’s dead body is hurled back down to lie, still. This shot proved something of a challenge. The stuntman flipping down from the floor above looked too agile for a corpse. After meeting of minds, including a red-shirted Raymond Chow, the crew managed to replicate a dead man falling. When The Brawler lies prostrate in the background, he’s ‘played’ by Bruce’s ‘butler’, the ubiquitous Wu Ngan.

It’s evident from these dailies that Lee the director faced his greatest challenge choreographing the fight between himself and Chi Hon-tsoi. Chi’s role in the earlier ‘Hapkido’ (1982), choreographed by Sammo Hung, was basically limited to the hapkido grandmaster performing an on-screen demonstration of his art. Lee had been introduced to Chi Hon-tsoi by their mutual friend Jhoon Rhee. Bruce always favoured Korean martial artists over their Chinese counterparts. He later persuaded Golden Harvest to cast taekwondo-ist Jhoon Rhee in the film ‘When Taekwondo Strikes’ (1973). As had been Lee’s plan for ‘Game of Death’, part of that film on location in Korea. Bruce was still alive when Jhoon Rhee flew to Hong Kong to shoot scenes for the movie at the Golden Harvest studios. Rhee remembers that, after he returned to the US, he had his last conversation with Bruce on the telephone. His friend called to tell him that ‘When Taekwondo Strikes’ (1973) was ready for release.

Lee met Chi Hon-tsoi, who was then teaching at Andrews Air Force Base in Maryland, when the latter gave a hapkido demonstration at Rhee’s International Karate Championships. Bruce later visited Chi at the Air Base to ‘absorb what is useful’ from his style. It was through this connection that hapkido proved so influential in the development of Golden Harvest’s’ ‘house style’ of martial arts action. The burly actor/stuntman/choreographer Sammo Hung became especially adept at this Korean art.

Besides Hung, the most famous of Chi Hon-tsoi’s movie students was Angela Mao, star of ‘Hapkido’ (1972). She visited her teacher on the set of ‘Game of Death’. Many decades later, Grandmaster Chi was reunited with his former protégé at her restaurant in Queens, New York.

Meanwhile, back in the 1972 ‘Game of Death’ footage, The Stylist, undeterred by The Brawler’s demise, makes a run for the stairs. He is then fended off by The Hapkidoist, who throws him around the room at will as Hai Tien just stands clear. Then it’s The Stylist’s turn to step aside as Lee’s character re-engages the Korean master.

As these two fight, The Stylist makes a second run for the stairs. This time, he mounts them successfully and finds himself on the floor above facing the final Guardian, The Unknown (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar). The Unknown is a towering African American fighter. With his first kick, The Unknown slashes open a hanging sandbag. Sand pours on to the tatami mats, and then down through it to the floor below, where it’s sprinkled onto Lee and The Hapkidoist.

As Lee continues his battle with The Hapkidoist, The Stylist realizes he’s no match for The Unknown. As he tries to run up the stairs to the floor above, his towering foe sky hooks him back down, and then holds him up by the neck. This a gag was achieved by suspending James Tien from a wire. The funniest clips on the ‘Game of Death’ dailies are those of Tien floating around the room. It’s curious that The Unknown prevents The Stylist from getting to the highest floor. Hai Tien, when he finally defeats the final Guardian, declines to ascend to the ultimate level.

After getting hurled across the floor by The Unknown (Kareem Abdul-Jabbar), The Stylist (James Tien) cries out in terror for Hai Tien to come to his rescue. Hai Tien finally defeats The Hapkidoist, breaking the man’s back, leaving him alive but crippled. As mentioned, Lee’s character in ‘Game of Death’ is the most casually brutal of any the actor played. Even when avenging his sister’s death in ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), Lee’s character feels something after he kills Oharra.

Hai Tien then runs up to the floor above, just in time to see the body of The Stylist being thrown from one side of the chamber to the other. The Stylist crashes to the floor and lies still. As Lee gapes at the sheer height of The Unknown, his towering opponent calmly sits back down in a rocking chair. Lee runs at The Unknown and gets kicked off his feet. This is where we see the cool shot that was, amazingly, cut from the 1978 version. Hai Tien is seen by The Unknown from a ‘rocking’ POV.

The duel proper begins. Hai Tien is initially kept at bay by his opponent’s extraordinary reach advantage. The smaller man battles gamely, but it’s only after he’s knocked backwards, breaking some panels of the pagoda ‘windows’, that the tide turns. Hai Tien realizes that his towering foe’s eyes are hyper sensitive to light. He breaks more panels and broad sunlight shines in. In the weirdest revelation of the ‘Game of Death’ dailies, The Unknown’s sunglasses are knocked off to reveal that he has pink-pupil ‘cat’s eyes’. We even get his pint-tinted POV. Realizing he now has the upper hand, Hai Tien does give this last opponent the choice of stepping aside. The Unknown insists on finishing their match. There are several points where it looks like Hai Tien could have run up the stairs unimpeded. Regardless, Hai Tien closes the distance, and finally applies a painstakingly slow chokehold that finally snaps his opponent’s neck. Again, he could just have choked the taller man out, jiujitsu style, but elects to kill him instead.

It seems that Hai Tien’s mission was to clear the way so that The Locksmith (Lee Kwan) could come up and retrieve the treasure. It had been theorized that this ‘treasure’ at the top of the tower was a book of mirrors, symbolizing the enlightenment of self-knowledge. This is an image borrowed from Lee’s earlier ‘The Silent Flute’ script. Bruce referred to the concept in his interview with Ted Thomas, “(Martial art) is like a mirror to reflect (oneself).” So why would Hai Tien leave the book of mirrors for the Locksmith and not wait to see it for himself? Especially after expending so much energy to attain it?

Instead, Hai Tien yells down to The Locksmith in Cantonese through the broken window panels, telling him it’s safe to come up. He listens to the off-camera response, and then wearily makes his way back down the pagoda, floor by floor. At the Temple of the Tiger, he breaks another window panel, yells again, and then keeps walking down the stairs and… The rest is silence.

Bruce was now entering into negotiations to make ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), putting ‘Game of Death’ on hold. At the time, he was apparently planning to return to the project after completing his Hollywood debut.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Over the years since I discovered these dailies, I’ve started to wonder if Lee would ever have finished ‘Game of Death’. Had he lived, Bruce, after the global success of ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), would have been flooded with offers. Even before that film’s release, he was fielding bids for his services from Italian mogul Carlo Ponti, neophyte producer Andy Vajna and many more. A swordplay epic for Shaw Bros? A Western with Steve McQueen? A sequel to ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973)? American audiences wanted this last so much that ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972) was released in the US as ‘Return of the Dragon’. With his hour finally upon him, would Bruce really have returned to this bizarre pet project? Perhaps it would have been reimagined as a docu-drama, an overview of Lee’s martial arts philosophy intercut with dramatic scenes from the 1972 ‘Game of Death’ footage.

After I first watched the long-lost footage in the Media Asia Archive, I emerged blinking into the bright sunshine of Kowloon Bay. Now I’d located the Holy Grail, what to do with it? There was one scenario where I could have kept quiet about my find and just retained the ‘lost’ ‘Game of Death’ footage for myself. I’d have told the SFC staff there was nothing of value on the tapes. The relevant reels would have gone back into the vaults, like the crate containing the Ark at the end of the first ‘Raiders’ movie. I’d just have run myself a VHS copy and slipped away night. I’d have been like that rich Bruce Lee fan in Hong Kong with his 12 minutes of ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972) outtakes, sitting alone in the moonlight, Gollum-style, holding my ‘precious’ footage.

At the time I chanced upon the ‘Game of Death’ dailies, no-one else seemed to even be looking for them. Even if there were, they weren’t looking in the right place. I could even have taken steps to make sure that the VHS tape I ran of the footage was the only copy to ever leave the Media Asia archive.

Except that I’m not that guy. After getting over the thrill of this discovery, my initial desire was to share it with the Bruce Lee fan community and, hopefully, the wider audience as well. Once I had my own copy on tape, I viewed and reviewed the material, trying to find a way to present it in some kind of commercial project. Almost as fascinating as the narrative content of the footage was the insight it offered into Bruce Lee at work, the endless repetitive takes in search of perfection, the brief glimpses of the activity on-set between scenes…

By now, of course, it’s all been Youtube-ed to death, but, at the time I found it, none of Lee’s fans had seen anything like this volume of ‘new’ footage of their idol since ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973) was released. Initially, my colleagues at Media Asia didn’t share my enthusiasm. As far as they were concerned, I hadn’t really found anything new. It was all ‘just’ footage from ‘Game of Death’, which, as far as most of the world knew, was a rather cheesy Bruce Lee film released in 1978. There weren’t even any entire extra scenes, just the equivalent ‘deleted’ or ‘alternate’ footage’ from an existing film, shot after shot of Bruce Lee in the same yellow tracksuit, fighting the same guys he fought in the 1978 version. It was the kind of stuff long-time fans liked as bonus features on a DVD. And so what? With some effort, I managed to persuade them that there might be a wider audience out there for this material. Despite some reservations, the Media Asia bosses gave me a tentative green light to try and exploit this material.

I then found myself in a position very similar to the one Robert Clouse had been in back in 1977. How to make a commercially accessible feature out of a roll of dailies from an unfinished film? The 1978 ‘Game of Death’ had sold very well all around the world. That’s why Golden Harvest went on to producing a sequel, known variously as ‘Game of Death 2’ (1981) or ‘Tower of Death’. Though mainstream audiences embraced ‘Game of Death’ (1978), with all its American B movie trappings, most Bruce Lee fans were very disappointed. They hated that Clouse had wrapped such a sub-standard Hollywood thriller around their idol’s final legacy. As I studied the surviving ‘Game of Death’ footage in detail, I felt more sympathy for ol’ Bob than I had before. I realized what a challenge Clouse had faced in 1977 when faced with the challenge of turning this material into something that would entertain a mainstream audience. He couldn’t just make a movie for the diehard Bruce Lee devotees. It had to play for the world.

My first instinct was to try to give the fans what they wanted. I would somehow find a way to shoot the film Lee would have made, had he lived to complete it. I had the ‘Game of Death’ outline. I had the original footage. And I was so much smarter than the late Robert Clouse. How hard could it be?

On reflection, I realized that the only chance to make a film that hewed close to Lee’s original vision had come and gone in 1973. This is how it would have to have happened:

Raymond Chow would have waited a suitable time after Lee’s funeral and the departure of Bruce’s family for America. He would then have announced that, to honor his late friend’s memory, Golden Harvest was going to do what Lee would have wanted and complete his unfinished masterpiece: ‘Game of Death’.

Chow often mentioned being frozen with grief, but this period of mourning didn’t stop him rushing the ‘Bruce Lee, The Man and The Legend’ (1973) documentary into production, nor did it prevent him from distributing ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973) throughout South-East Asia. It would have seemed the most natural thing in the world for Golden Harvest to resume production of ‘Game of Death’ in 1973. Raymond could have followed Bruce’s notes and used another actor, someone like Don Wong Tao, star of ‘Slaughter in San Francisco’ (1974), to perform the scenes Lee didn’t live to shoot.

Would audiences have accepted someone imitating Bruce Lee? They did when Golden Harvest finally released the Robert Clouse version of ‘Game of Death’. And they got away with that in 1978. Back in 1973, audiences worldwide would have paid to see footage of Bruce painting his house. No-one would have blinked at a film in which another Chinese actor played the lead for those scenes Lee hadn’t lived to shoot.

And, in 1973, Lee’s original ‘Game of Death’ sets could easily have been reassembled on a Golden Harvest studio soundstage. James Tien, Chieh Yuan and the rest of the supporting cast were all still alive and looking pretty much as they had when Bruce filmed them. And they could have used George Lazenby in ‘Game of Death’, rather than ‘Stoner’ (1974), casting him in the role Lee had originally intended for him. Lee Kwan was on hand to play The Locksmith. Throw in Sammo Hung as choreographer and as a Challenger, and “this man’s putting quite a collection together.”

A version completed in 1973 would have been very different from the film they made in 1978. Maybe it would have lacked the gloss of the Robert Clouse film, but a 1973 version, a new Bruce Lee movie released in the wake of ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), at the height of the global kung fu craze? That film would have been a huge hit everywhere.

So why didn’t Golden Harvest act sooner? [redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

Hong Kong cinema later experienced fascinating challenge similar to the one described above. In 1989, director/producer Tsui Hark put together what he hoped would be a comeback film for his idol, King Hu. The latter had made his name with the ground breaking ‘Come Drink with Me’ (1966), but, when Tsui approached him to direct ‘Swordsman’ (1990), hadn’t made a film for six years. Once production began, Tsui realized that King Hu’s fragile health wouldn’t allow him to shoot a wu xia film of this scale. Rather than abandon the project, Tsui employed five other directors, including himself, and urged them to try to channel the spirit of King Hu as they shot their scenes for the film. The fact that there were so many of them meant that no one director could be accused of stealing King Hu’s thunder. Perhaps Raymond Chow should have employed a similar strategy in 1973. He could have coerced Wong Fung (‘Hapkido’ (1972), Cheng Chang-ho (‘King Boxer’ (1972) and perhaps even King Hu (‘A Touch of Zen’ (1971), then starting his career at Golden Harvest, to each shoot one level of the missing pagoda scenes, each channeling the spirit of Bruce Lee as they did so… It was not to be.

By the time I found the footage, a further two decades had passed, and it felt even less feasible to just shoot Lee’s original concept using another actor for the missing scenes. My second concept was to try and come up with a framing device that would allow an edited version of Lee’s original footage to play in its entirety. I wrote a treatment that began years after the events depicted in the 1972 ‘Game of Death’ footage. The ‘Island of No Guns’ still exists with its temple and the five storey pagoda. Each year, new Guardians arrive to protect the different floors and new Challengers come to fight for the treasure. In my treatment, a prospective young Challenger seeks out the few masters who have survived these earlier ‘Game of Death’ adventures to learn how they did it.

The framing sequences would have an intentionally retro 70s kung fu movie vibe. The new young Challenger would seek out aged up versions of various Golden Harvest martial arts heroes like Sammo Hung, Byong Yu, Carter Wong, Dorian Tan and Angela Mao. He would travel to various locales across Asia. Each master would impart a different lesson, accompanied by a flashback to their unique experience in the pagoda. I started looking at obscure Golden Harvest titles, trying to find classic fight sequences set in and around similar pagodas. There were a lot. ‘Hapkido’ (1972) star Carter Wong fighting ‘Game of Death’ performer Chi Hon-tsoi in John Woo’s ‘The Dragon Tamers’ (1975). Byong Yu dueling Whang In-shik outside such a tower in ‘The Association’ (1975). Angela Mao and Tan Tao-liang fighting Chan Sing in ‘The Himalayan’ (1976). In the 1996 footage, each of these masters would teach our hero, physically and philosophically, a different aspect of martial arts.

Finally, the Challenger tracks down the only man to make it to the top of the pagoda, and this would be our Bruce Lee character, Hai Tien. He would be an old man now, obviating the need to have a young Bruce Lee lookalike. The ‘old’ Hai Tien would provide a voice-over explaining the events surrounding his own experiences at the tower, as we dissolve to an edited version of Lee’s footage. At the end, the old man has succeeded in imparting to the young Challenger the essence of Lee’s Jeet Kune Do adapt or die philosophy. We would then see this new warrior outside the pagoda, about to begin his own ascent. If this newcomer had made enough of an impact, perhaps we could spin off a ‘New Game of Death’ movie depicting his adventures.

I thought to approach Quentin Tarantino, whom I knew en passant, to direct the new footage, and produce the entire project. The actor I had in mind for the role of the new Challenger was Donnie Yen. I felt he had huge potential, but Donnie’s film career was then at a low ebb. I never got to make my ‘Game of Death’ with him, but his charatcer did fight his way up the levels of a pagoda in his TV series ‘Kung Fu Master’ (1994).

My second concept was even more meta in its ambition. A young martial arts expert becomes obsessed with the fate of a former kung fu movie star who began shooting his masterpiece, then disappeared before completing it. Through mysterious circumstances, our hero finds himself the sole owner of the surviving footage, and is told that the clues to the missing star’s fate lie hidden in the footage itself. Our hero sets off to find the truth, and finds the experiences he has along the way mirror the challenges faced by his idol’s character in the film footage he possesses. His journey leads him to a deeper understanding of martial arts. In the end, he finds the former movie star, the Bruce Lee character, who has abandoned the glitz of the film world to study in seclusion. The sage left the clues in his unfinished work in the hopes that a worthy successor would seek him out. He accepts our hero as his student and they begin to train together.

I pitched both of the above vehicles for the surviving ‘Game of Death’ footage, as well as several even less well realized concepts. My Media Asia colleagues felt that, even with a minimal amount of new footage shot, this would be too expensive a venture for them. I was given permission to try and find a partner company with whom we could co-produce such a project. One such prospective partner arrived in the form of Artport, a Japanese production/distribution company. My friend Nishi, a Japanese uber-fan of Bruce Lee, introduced me to Jun’ichi ‘Jimmy’ Matsushita, the head of Artport. Jimmy himself was a long-time karate exponent and also a devotee of Bruce Lee. When he came to visit our Hong Kong office, the Artport boss, who spoke no English, delivered a half hour lecture to the bemused Media Asia executives, explaining how Bruce Lee had changed his life, even rising from his chair to demonstrate his martial arts skills. He offered to break some bricks for us, but sadly there were none to hand.

This was actually not the most unnerving Bruce Lee related conversation to take part in the Media Asia boardroom. Some months earlier, a pair of Japanese producers had come to pitch the company about us partnering up to produce a new film about Bruce Lee. This, they assured us, would free the spirit of Bruce Lee, currently trapped on Earth, to travel to the afterlife. “You mean, that’s what happens in the movie?” No, they assured us gravely. In reality. A great Buddhist master in Japan had told them that they needed to make their film to free the spirit of Bruce…

After Jimmy Matsushita’s memorable display, I was left to negotiate a deal for Artport to acquire the Japanese rights to the ‘Game of Death’ material. There was little actual negotiation. Mr. Matsushita wrote down a number on a scrap of paper and then handed it to me. This was his offer, take it or leave it. It was much, much higher than anyone could have anticipated. I told Jimmy I had to get permission from Thomas Chung, the sometimes irascible Media Asia boss, before I could sign off on a deal of this size. When I showed the paper to Thomas, he cursed me and my (admittedly) poor math skills, accusing me of putting the decimal point in the wrong place. Finally, Jimmy himself convinced Thomas that this was, indeed, his intended offer. It was signed on the spot. I never again saw an offer for a Media Asia project accepted with anything like that kind of speed.

Over a copious amount of sake in a hotel bar, I managed to outline my own ideas for ‘Game of Death’ to Jimmy and Nishi-san. They seemed to respond favourably to the idea of a new star investigating the fate of the ‘Bruce Lee’ figure. I anticipated working with the Artport team to further develop the concept. I was to be disappointed. After Jimmy returned to Tokyo, it became clear he wanted to run his own ship, and God knows he’d paid for the privilege. It took some doing, but Artport finally managed to make a version of ‘Game of Death’ that was even more incoherent that the 1978 version. Or, indeed, any of the concepts I’d pitched them.

The Artport ‘G.O.D’ (2000), directed by Toshikazu Okushi, opens with the screening of dailies from the Bruce Lee/Kareem Abdul-Jabbar fight. A young Chinese woman (Tiffany Lee) provides a rather fractured running commentary. In a dramatized sequence, we see Bruce Lee (David Lee) and his producer discuss the ‘Game of Death’ shoot. Bruce justifies the experimental nature of his new project. These scenes were shot at Clearwater Bay Studios, where Jean-Claude Van Damme had shot ‘Bloodsport’ (1988) and Donnie Yen filmed his ‘Fist of Fury’ (1995) series. We see ‘Bruce’ in his office sketching his designs for ‘Game of Death’, and then dissolve to an animated sequence that illustrates the concept of the film.

In a Cantonese language interview, actor/stuntman Yuen Wah remembers his experiences working with Bruce Lee and shooting the outdoor sequence for ‘Game of Death’. This is intercut with footage of Yuen Wah demonstrating Bruce Lee style screen combat against an Irish martial artist named Marc Redmond. Marc was someone I had hired for ‘Gen-Y Cops’ (2000), a film on which I worked as a writer and producer for Media Asia.

After this documentary interlude, we return to the plot, and see Lee’s sometimes antagonistic relationship with the local press, his close bond with his family, his co-workers expressing their doubts about his ‘Game of Death’ project… Bruce fights a couple of challengers. These dire, incoherent scenes compare unfavorably with the later CCTV ‘Legend of Bruce Lee’ (2008) series, which proved a ratings hit in China. Next, Chaplin Chang, assistant director on ‘The Way of the Dragon’ (1972) and production manager on ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973), discusses his experiences with Lee. We see the Bruce Lee character choreographing the ‘Game of Death’ action, and then cut to the edited material from the original dailies.

‘G.O.D’ (2000) features the surviving footage of Dan Inosanto fighting Chieh Yuan, taken from the ‘Bruce Lee, The Man and The Legend’ (1973) documentary. There is also a new interview with Inosanto himself, filmed in LA. Dan recalls the challenge of keeping a grip on prop weapons in the humidity of Hong Kong. This is why most of the swords seen in period Chinese action films have 20th century gaffer’s tape wrapped around their handles. For the Artport project, Inosanto dubbed his own voice for his dialogue scenes with Bruce. In this cut of the footage, the Hapkidoist specifically instructs Bruce Lee’s character, Hai Tien, to throw his nunchaku away before they fight.

Though I wasn’t at all involved in the actual production of this odd docu-drama, I did make an unexpected contribution to the film. Once the Artport ‘G.O.D’ (2000) project was finished, Nishi-san called and asked if I would come into a Hong Kong recording studio and dub the Bruce Lee dialogue for the film. This request stemmed from an occurrence at the annual event we used to hold for Japanese Bruce Lee fans at the BP Hotel in Tsim Sha Tsui. The projector broke down and so, to keep the audience entertained, I delivered some lines of ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973) dialogue in my best ‘Bruce Lee’ voice. Nishi was in the audience, and apparently decided then and there that I was the man for the job.

My first reaction to Nishi’s request was that it would take some nerve for me, a white guy from Peterborough, England, to dare re-voice the greatest Chinese icon of the 20th century. What swayed me was the reality that, if I dubbed Lee myself, I could at least be part of the process and try to make sure the performance was decent. They were going to have to dub the footage anyway. And so it came to pass that, after all those years of researching the ‘Game of Death’ footage to find out what Lee was trying to say, whatever it was he said would now be said by me.

My recording session took just one evening at a Mong Kok studio. You may wonder how and why I had developed my passable Bruce Lee impersonation. Years earlier, Kung Fu Monthly magazine had released an audiocassette of Lee being interviewed by Hong Kong journalist Ted Thomas. The same tape also had Bruce Lee performing dialogue from the missing ‘monk scene’ shot for ‘Enter the Dragon’ (1973). There was also an odd ‘Desert Island Discs’ section with Bruce’s widow, Linda, being interviewed by veteran DJ ‘Uncle’ Ray Cordeiro. Cordeiro’s ‘All The Way with Ray’, had started broadcasting in 1970, and went on to become the longest running show in radio history. Linda selected the favorite songs of herself and her late husband (‘My Way’, Blood, Sweat and Tears…) between interview segments. The show was recorded in the Lee family home on Cumberland Road shortly after Bruce’s passing, with Cordeiro describing the different items displayed in the house.

I had listened to that Bruce Lee interview and to Lee’s movie dialogue incessantly. Since then, I had spent years in an environment filled with folk who, like Bruce Lee, spoke English with a Cantonese accent. I can also sing a bit, which helps when you’re trying to talk like Bruce Lee, who often seemed to be performing, rather than simply acting, his English dialogue.

My contribution to the Artport ‘G.O.D’ (2000) project led to my being hired by another Japanese company to perform Bruce Lee’s voice for an instructional videogame. This game taught the players how to type long words faster to avoid being hit by Bruce Lee, or his opponents. I had to deliver typing instructions in a Bruce Lee voice (“The left fingerrrr to the right key paaaaad. Thaaaat’s iiiittt…”). To my surprise, the game proved very successful, and topped the Japanese chart for ‘non bash-‘em-up’ games.

Looking at the finished ‘G.O.D’ (2000), I was very disappointed with the way Artport presented their hard-earned ‘Game of Death’ footage. It was a lost opportunity to do something truly memorable with the material. There’s no question that their creative team had its heart in the right place. I think the biggest problem is that the finished film absolutely reflects the rather odd character of Artport’s founder.

At that time, I was working at Media Asia and moonlighting for a UK-based home entertainment company, Medusa, later to become known as Showbox. One Cantonese reading of my name ‘Bey Logan’ is ‘doing moonlighting’, so it makes sense that I always had a few irons in the fire. Medusa had a label called Hong Kong Legends, and the way they repackaged and released these films set a new industry standard. It seemed unlikely I would now be able to produce my own ‘Game of Death’ feature. I decided that I would just do all I could to make the footage available to the fans. The best presentation of the footage was on the re-edited version we used as a bonus feature on the Hong Kong Legends DVD release of ‘Game of Death’ (1978). That, at least, was pure Bruce Lee, with nothing added or taken away.

It was only to be expected that John Little, then expert-in-residence at the Bruce Lee Estate, would hear that the long-lost ‘Game of Death’ footage had resurfaced. John was desperate to get his hands on it. He could never quite forgive himself for not finding the footage first. I was persona non grata with the Lee Estate at the time. This was largely, I suspect, due to one line in one review I wrote concerning one of John Little’s books on Bruce Lee. I took issue with that fact that John was promoting Lee as some kind of Deepak Chopra style self-help guru, using Bruce’s example to preach family values. John Little himself is and was a wonderful proponent of those traditional Canadian ethics. His biggest shortcoming as a researcher was a desire to impose his own beliefs onto those of his subject.

[redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

So there was no question of my personally cooperating with the Bruce Lee Estate on a ‘Game of Death’ project. What concerned John Little was that I might sell the precious ‘Game of Death’ footage to someone else, potentially his sworn rival, the Australian documentarian Walt Missingham. Worst still, I might yet produce my own ‘Game of Death’ project, leaving him and the Estate out in the cold. And he was absolutely right. If I could have got Media Asia to back my version of ‘Game of Death’, I would have made it. The company had doubts about the commercial potential of such a project, compared to the immediate revenue obtained by licensing it out. Given the subsequent lukewarm response to Little’s ‘Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey’ (2000), I can see that they may have been right. Incidentally, if Walt Missingham had made a better financial offer than John Little, I would absolutely have sold the footage to him instead.

Reasoning, correctly, that I might have my own agenda, John Little began calling any Media Asia executive that he could find the phone number for, campaigning to buy the exclusive North American rights to the footage. Little also assumed that I still bore a grudge over the Reviewgate matter. In exasperation, my Chinese colleagues, one by one, put their heads around my office door and said “This damn gweilo (foreigner) keeps bothering us. You found this bloody footage, Bey. You handle him!”

I dutifully called John Little in the States. “I would be delighted to sell the footage to you,” I told him, to his considerable surprise. “So make me an offer.” John duly did so, and we closed the deal quite quickly. I think we got a slightly better than fair price. I didn’t make unreasonable demands, but I didn’t give John a discount either. And I didn’t do him any favors. I admit I was still disappointed not to be able to finish the ‘Game’ myself. And I didn’t like to the way John Little had tried to do an end run around me at Media Asia. John asked that we include clips from Lee’s other films in the deal, but I held the line that he would have to pay our rather high licensing rates for anything outside of the 1972 ‘Game of Death’ material. It was for this reason that the footage of Dan Inosanto fighting Chieh Yuan, found only in the ‘Bruce Lee, The Man and The Legend’ (1973) documentary, doesn’t appear in Little’s ‘Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey’ (2000) project. Looking back, I realize I was being petty in my dealings with John Little, who, when we finally met in person, turned out to be a charming man. He can be perhaps slightly over earnest, but also has a wry sense of humour and a genuinely kind nature. If I had it to do over, I’d give John whatever he needed for his film.

John Little prevailed upon Warner Bros home video executive Brian Jamieson to have that company finance his ambitious ‘Game of Death’ project, ‘Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey’ (2000). It was to be directed, in Korea, by Little himself. Brian Jamieson is the patron saint of film restoration, and his work on Sam Peckinpah’s ‘Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid’ (1973) alone earns him his place in cineaste heaven. John Little is perhaps alone in the belief that he is a film director manqué. He set out to shoot drama scenes in Korea that would represent the ‘Game of Death’ scenes Bruce Lee did not live to film. Little’s new footage would then be put into the context of a documentary detailing the genesis of Lee’s ‘Game of Death’ project.

After John Little delivered his cut of the film, Warner Bros decided the project would work best purely as a documentary. Most of Little’s dramatic material was relegated to ‘deleted scenes’ on the DVD release. Little also fell victim to the bitter internecine rivalry been Jamieson’s domestic America division and the international branch of the company. Unavoidably, there was a jarring discrepancy between the footage Lee had shot in 1973, and the footage John filmed in Korea, which feels more like a local Hong Kong TV series. Years later, Mainland Chinese broadcaster CCTV did produce their own Bruce Lee show, ‘The Legend of Bruce Lee’ (2008), and recreated the 1972 ‘Game of Death’ set and action therein.

John Little managed to secure new interviews with ‘Game of Death’ performers Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Chi Hon-tsoi. He also had them dub their own dialogue for the ‘restored’ version of the footage. Dan Inosanto was notable by his absence. This was due to the fact that John was perceived as being a representative of the Lee Estate, who had treated Dan so atrociously during the formation of the Jeet Kune Do Nucleus.

Despite the long anticipation among fans hungry for ‘new’ Bruce Lee material, ‘Bruce Lee: A Warrior’s Journey’ (2000) didn’t perform as expected. It contributed to the declining relationship between John Little and the Lee Estate. In effect, Little proved Media Asia right and myself wrong. The found footage was too much of the same old ‘Game of Death’ to attract mainstream audiences. [redacted – to read more: buy the book HERE]

In 2007, ‘Fast and Furious’ series director Justin Lin shot a passion project called ‘Finishing The Game: The Search for a new Bruce Lee’. A lifelong Lee fan, Lin had, like the rest of us, obsessed about the lost 1972 ‘Game of Death’ footage, and the challenge Golden Harvest faced in, well, finishing ‘The Game’. In this hit and miss mockumentary, various wannabes vie for the chance to play Billy Lo (or a reasonable facsimile thereof). Nor was Lin done with his reverence for all things Bruce. In ‘2018’, he produced a TV series based on Lee’s unmade ‘Warrior’ concept.

By the various means described above, Bruce Lee’s ‘Game of Death’ footage was finally made available to audiences around the world, to fans who were born years after Lee’s passing. I’m proud that I had a part to play in reclaiming this previously lost aspect of his legacy.

| There are no products |